A few months back, I began exploring how to build a movie-themed chatbot. The idea was simple: create a web API that could be connected to a chatbot front end and enable users to hold real conversations about movies, interacting with a Semantic Search API I’d previously built (the BONO Search API). I started with the basics: natural language queries, a .NET backend, and a connection to Azure OpenAI.

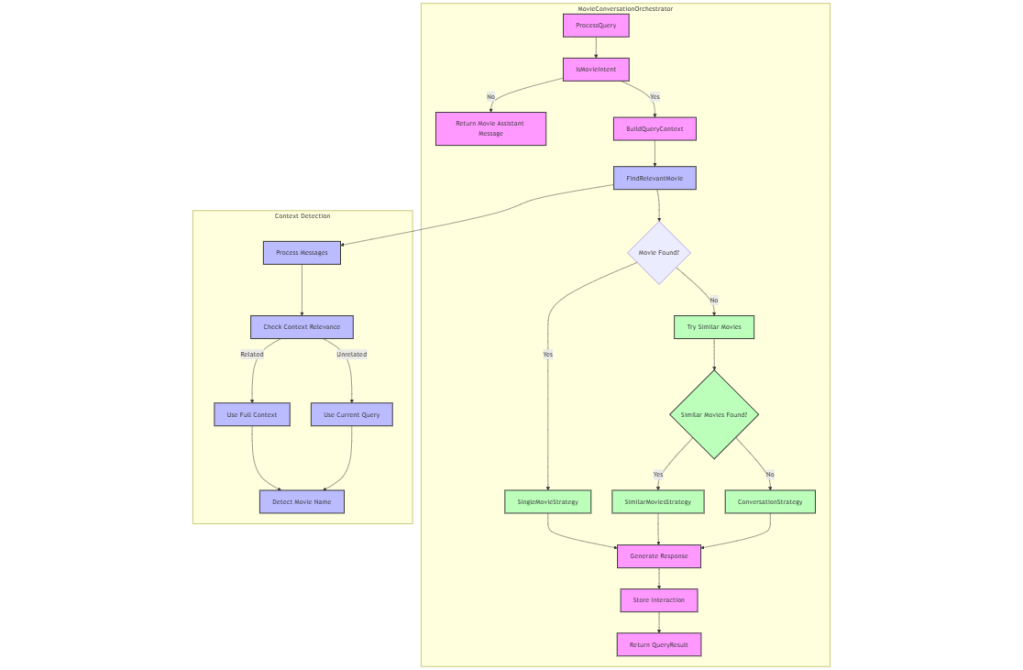

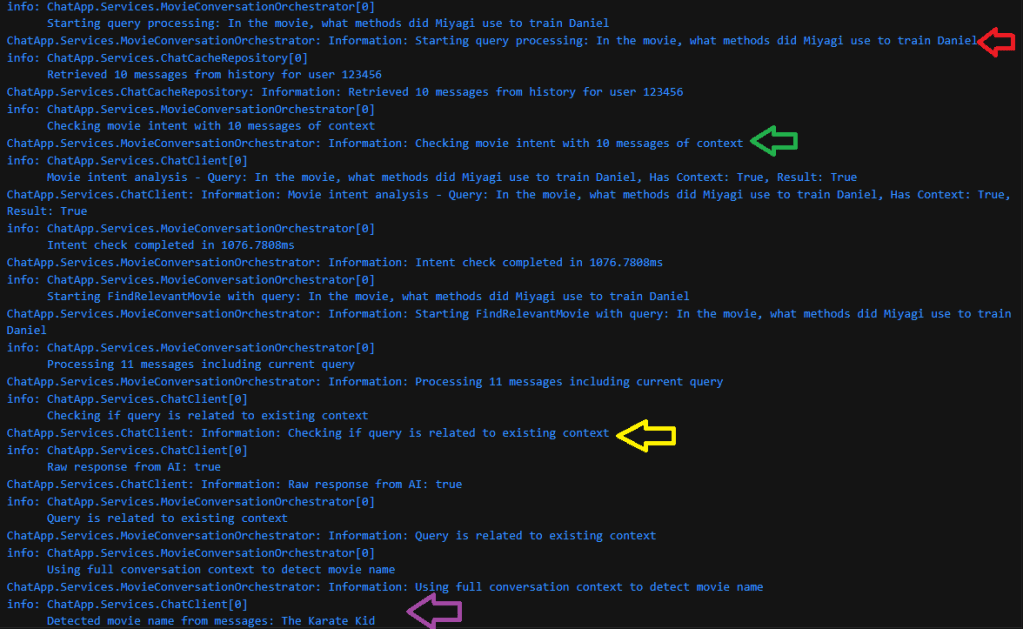

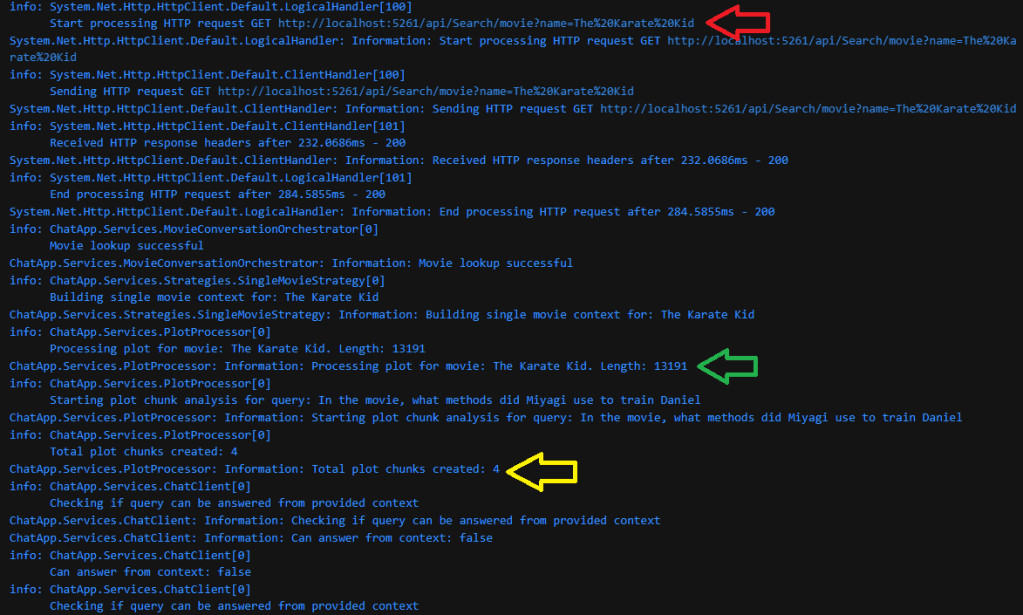

The first incarnation of my API, called RobotoAPI, worked by using a manually written Orchestrator. Its job was to steer each user query toward an appropriate response from GPT-4, either by injecting relevant plot data into the LLM’s context window using Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), or by gracefully providing a fallback response if the user wandered too far off topic. Getting a response from the LLM was (thanks to Azure OpenAI) the easiest part. The real challenge was in managing large chunks of context, anticipating the many directions a conversation might go, and engineering prompts robust enough to handle it all. It took several iterations before I landed on something that felt “conversational.”

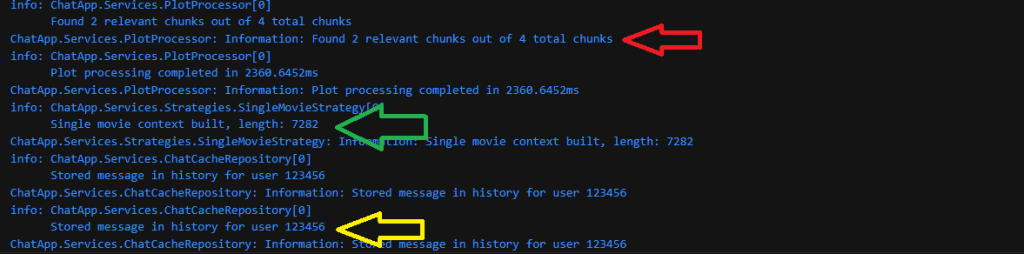

To create a more natural, conversational flow, I brought in Redis to store and retrieve chat history. This allowed the API to “remember” past queries and responses, simulating a true back-and-forth conversation.

As a learning exercise, the project was hugely valuable. But even as RobotoAPI became more capable, I realized my approach wouldn’t scale cleanly. Each new conversation pattern meant more tangled code, and my orchestrator was starting to feel like a bottleneck.

That’s when I heard about Semantic Kernel, an open source library from Microsoft designed to make it easier to compose and orchestrate LLM-powered agents. I decided to check out Microsoft’s official learning path, and it turned out to be a fantastic introduction to not just the library itself, but to the concepts behind building agentic, modular chat systems. Semantic Kernel solved all the limitations I’d run into when building the RobotoAPI, and gave me a much cleaner foundation for what came next.

What is an Agentic System?

At its core, an agentic system is about giving a large language model more autonomy. Instead of just using the LLM to generate text, we treat it as a “reasoning engine” that can make decisions and take actions. The word “autonomy” is used quite often to describe an agentic system but what does that exactly mean?

Think of it like this:

- A simple RAG system is like a helpful librarian. You ask a question, and they go to a specific shelf (the “strategy”), pull out a book (the “data”), and give it to you to find the answer.

- An agentic system is like a team of expert researchers. You give them a complex question, and they work together to solve it. One researcher might be an expert in finding sources, another in analyzing data, and a third in synthesizing the final report. They can talk to each other, share information, and adapt their plan as they go. In an agentic system, we give the LLM access to a set of “tools” (which are just functions in our code) and a goal. The LLM’s job is to figure out which tools to use, in what order, to achieve that goal.

The Power of Autonomy: From switch Statements to Smart Decisions

To truly appreciate this shift, let’s think about how we, as developers, traditionally handle branching logic. Our instinct for managing different inputs is often to reach for a switch statement or a series of if-else blocks. This approach is incredibly effective when you have a predictable, finite set of inputs. If you’re processing payment types, you can have a case for “CreditCard”, “PayPal”, and “BankTransfer”. It’s clean, reliable, and easy to understand.

But what happens when the input isn’t a neat, distinct value, but messy, ambiguous human language?

How would you write a switch statement to handle a user’s query about movies? You could try to check for keywords. A case for “plot”, a case for “actor”, a case for “director”. But this is brittle. What if the user asks, “What was that film about?” or “Who were the stars in it?” or “Tell me a movie like Blade Runner”? the semantic variations are nearly infinite. You would be trapped in a never-ending cycle of adding new cases, and your code would become an unmanageable mess.

This is where an agent’s autonomy fundamentally changes the game.

Instead of a developer trying to pre-define every possible logical path, we empower the LLM to create the path on the fly. The agent doesn’t rely on matching specific keywords; it uses its deep understanding of language to interpret the user’s intent. It reads the sentence, understands the underlying meaning, and then selects the appropriate tool for the job. The agent’s power lies in its ability to handle the boundless variety of human expression, something a switch statement, by its very nature, cannot do.

Introducing the New RobotoAgentAPI

With this new approach in mind, I rebuilt my movie chatbot API as a completely Agentic version. The new RobotoAgentAPI is a multi-agent system that uses the Semantic Kernel framework to orchestrate the work of two specialized agents: a ChatAgent and a SearchAgent.

Setting the Stage with Semantic Kernel

The magic begins in the application’s startup file, Program.cs. This is where we build our “Kernel” and tell it about the agents and their tools. In the Microsoft Learn path I mentioned earlier, the examples there were given in Python but translating the same code into C# is pretty straightforward.

1 // In Program.cs

2

3 // ... other services

4

5 // Configure Semantic Kernel

6 builder.Services.AddSingleton<Kernel>(sp =>

7 {

8 // Configure the connection to our LLM (Azure OpenAI)

9 var kernel = Kernel.CreateBuilder()

10 .AddAzureOpenAIChatCompletion(

11 deploymentName: "o3-mini",

12 endpoint: openAiEndpoint,

13 apiKey: openAiKey)

14 .Build();

15

16 // Get the services our agents will need

17 var chatCompletion = kernel.GetRequiredService<Microsoft.SemanticKernel.ChatCompletion.IChatCompletionService>();

18 var searchAgentPlugin = sp.GetRequiredService<SearchAgentPlugin>();

19

20 // Create an instance of our ChatAgent

21 var chatAgentPlugin = new ChatAgentPlugin(chatCompletion, searchAgentPlugin);

22

23 // IMPORTANT: Register our agents and their tools with the kernel

24 kernel.ImportPluginFromObject(chatAgentPlugin, "ChatAgent");

25 kernel.ImportPluginFromObject(searchAgentPlugin, "SearchAgent");

26

27 return kernel;

28 });

The key starting point here is kernel.ImportPluginFromObject(…). This line tells the Semantic Kernel to inspect the ChatAgentPlugin and SearchAgentPlugin classes and make all of their public methods available as “tools” that the LLM can call. Earlier in the specify to the kernal our LLM parameter such as openAiEndpoint, openAiKey and the deploymentName. For my example, o3-mini was a suitable choice as it has a decent context window (for large movie plot data) but is more cost effective than the large models. It is also a reasoning model which improves the overall agentic workflow performance.

Defining the Agents as “Toolboxes”

The plugin classes are the “toolboxes” for the LLM. Each tool is a C# method decorated with a [KernelFunction] attribute. More importantly, each tool has a [Description] attribute.

This is the most critical part. The description is not for developers; it’s the signpost the LLM reads to understand what a tool does. A clear, descriptive prompt is the key to enabling the AI to make smart, autonomous decisions.

Let’s look at a snippet from our SearchAgentPlugin.cs:

1 // In Agents/SearchAgentPlugin.cs

2

3 public class SearchAgentPlugin

4 {

5 // ... (constructor and other properties)

6

7 [KernelFunction]

8 [Description("Extract specific movie titles mentioned in a user query")]

9 public async Task<string> ExtractMovieNamesFromQueryAgentic(

10 [Description("The user's query to analyze for movie titles")] string query)

11 {

12 // ...

13 }

14

15 [KernelFunction]

16 [Description("Search for specific movies by their exact titles")]

17 public async Task<string> SearchMoviesByName(

18 [Description("Comma-separated list of movie titles to search for")] string movieNames)

19 {

20 // ...

21 }

22

23 [KernelFunction]

24 [Description("Check if a query relates to recently discussed movies in the conversation")]

25 public async Task<string> CheckRecentMovieContextAgentic(

26 [Description("The user's current query")] string query,

27 [Description("Recent conversation history")] string conversationHistory = "")

28 {

29 // ...

30 }

31 }

By decorating these methods with [KernelFunction] and providing clear descriptions for these functions as well as each parameter, we’ve created a set of tools that the Semantic Kernel can present to the LLM. When the LLM needs to accomplish a task, it will look through the descriptions of all available tools and pick the one that best matches its current need.

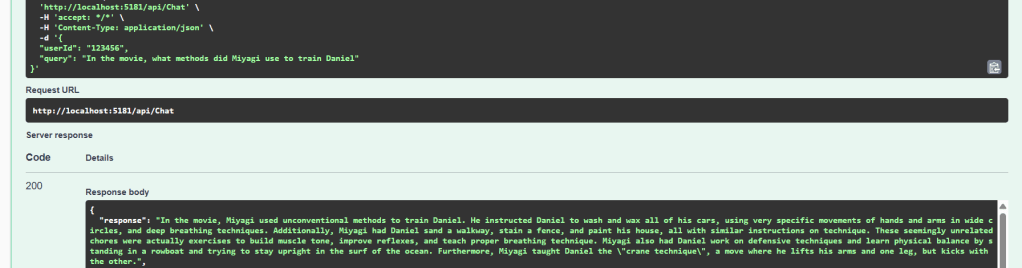

Putting It All Together: An Example in Action

Now, let’s see how this system truly shines by looking at the fully autonomous agentic flow. In the RobotoAgentAPI, there’s a special endpoint (/api/chat/agentic) that hands over almost all control to the AI. The C# code in the ProcessMessageAgentic function doesn’t contain a rigid, step-by-step plan. Instead, it simply does two things:

- It prepares the context by loading the user’s conversation history.

- It tells the Semantic Kernel: “Here is the conversation history and the user’s latest message. Your goal is to provide a helpful response. You have access to all the tools in all the registered plugins. Decide for yourself how to best achieve the goal.”

In the following code excerpt from the ChatContoller shows how simple it is to setup the Chat Agent and pass it the user’s query to get a response. In the code, we indicate the chat agent method we will use is “ProcessMessageAgentic” to first process the message but thereafter we leave the Chat Agent to “decide” which of the registered Kernal Functions it has available will be called to solve the user’s query.

// Use the ChatAgent plugin with agentic processing

var chatAgent = _kernel.Plugins["ChatAgent"];

if (chatAgent == null)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[AGENTIC] ERROR: ChatAgent plugin not found!");

return StatusCode(500, new ErrorResponse

{

Error = "PluginNotFound",

Message = "ChatAgent plugin not found",

Details = "The ChatAgent plugin is not registered"

});

}

var chatArguments = new KernelArguments

{

["message"] = request.Query,

["userId"] = request.UserId ?? "default"

};

var chatResult = await chatAgent["ProcessMessageAgentic"].InvokeAsync(_kernel, chatArguments);

if (chatResult?.ToString() != null)

{

var resultString = chatResult.ToString();

// Parse the result to extract the intelligent response

try

{

var movieResponse = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<MovieResponse>(resultString);

var textResponse = movieResponse?.IntelligentResponse ?? "I'm sorry, I couldn't process your request.";

return Ok(new ChatResponse { Response = textResponse });

}

catch (JsonException jsonEx)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[AGENTIC] JSON parsing failed: {jsonEx.Message}");

return Ok(new ChatResponse { Response = $"Raw response: {resultString}" });

}

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine($"[AGENTIC] Result is null or empty");

return Ok(new ChatResponse { Response = "No response from agentic processing" });

}

}

Let’s trace our conversation again through this new, more powerful lens. Here’s a typical movie related query:

User: “Tell me about the movie Fight Club.”

ChatController: The request hits the /agentic endpoint. It invokes the ChatAgent.ProcessMessageAgentic function.ChatAgent: The agent prepares the chat history (which is empty at the start), adds the user’s new message, and essentially tells the Kernel, “Your turn.”- Kernel + LLM (The Autonomous Part): The LLM now takes control. It analyzes the user’s request and scans the descriptions of all available tools from both the ChatAgent and SearchAgent.

- Reasoning: “To answer this, I first need to identify the movie title.”

- Tool Selection: It sees the SearchAgent.ExtractMovieNamesFromQueryAgentic tool. The description, “Extract specific movie titles mentioned in a user query,” is a perfect match.

- Action: It calls the tool. Result: The string “Fight Club”.

- Reasoning: “Great, I have the title. Now I need to find information about this movie.

- Tool Selection: It scans the tools again and finds SearchAgent.SearchMoviesByName. The description, “Search for specific movies by their exact titles,” fits perfectly.

- Action: It calls the tool with the title “Fight Club”. This function calls the external movie API. Result: A JSON object containing the plot, year, and other details for Fight Club.

- Reasoning: “I have the data. Now I must synthesize this information into a helpful, natural-language response for the user.

- Final Response: The LLM generates a summary of the movie based on the data it found and returns this single, coherent paragraph. This final text is sent back to the user, and the entire exchange is saved to the conversation history.

The key here is that the LLM, not the C# code, created the plan: Extract Name -> Search by Name -> Synthesize -> Answer.

Now, let’s see how it handles the crucial follow-up question.

User: “Was Tyler Durden real?”

ChatController->ChatAgent: The new query is passed to the ProcessMessageAgentic function as before.ChatAgent: The agent prepares the context. This time, it loads the history, which contains the previous turn about Fight Club, and adds the new question. It then hands control back to the Kernel.- Kernel + LLM (The Autonomous Part): The LLM analyzes the new request, but this time it has the vital context from the chat history.

- Reasoning: “The user’s query, ‘Was Tyler Durden real?’, doesn’t contain a movie title. However, the conversation history is about Fight Club. The new question is likely related to that.”

- Tool Selection: It scans its tools. SearchAgent.CheckRecentMovieContextAgentic, with the description “Check if a query relates to recently discussed movies in the conversation,” is the ideal tool to confirm this hypothesis.

- Action: It calls the tool, providing the new query and the history. Result: An analysis object confirming with high confidence that the query is about Fight Club.

- Reasoning: “My hypothesis was correct. The user is asking about a character in Fight Club. I have the plot details in my context from the previous turn. I will now analyze that plot to answer the specific question about Tyler Durden’s existence.”

- Final Response: The LLM analyzes the plot, understands the twist, and formulates a detailed explanation of the relationship between the narrator and Tyler Durden. This complete answer is sent back to the user.

In this second turn, the LLM devised a completely different plan: Check Context -> Analyze Existing Data -> Synthesize Answer. This ability to dynamically create and execute plans based on context is the essence of a truly agentic system and is a world away from the rigid logic of if-else or switch statements. Having the Chat Agent govern the conversation such that it is only about movies ensures the user is notified if they stray off topic.

As mentioned before, a huge benefit of Semantic Kernel is it’s ability to maintain a chat history, which saves us from trying to reinvent this logic each time. The chat history is vital for maintaining the conversation flow and keeping the “turn by turn” conversations within context. A second benefit, and equally important, is Semantic Kernel’s ability to automatically chunk the data from it’s history into the LLM.

A final point to mention on the Semantic Kernel code set would be the following line :

var executionSettings = new OpenAIPromptExecutionSettings

{

ToolCallBehavior = ToolCallBehavior.AutoInvokeKernelFunctions

};

//

var aiResponse = await _chatService.GetChatMessageContentAsync(

chatHistory,

executionSettings,

kernel);

The ToolCallBehavior.AutoInvokeKernelFunctions setting is what indicates to Semantic Kernel that you want to run Kernel Functions autonomously and this needs to be specified as part of the execution settings when calling the GetChatMessageContentAsync method of the chat service.

Conclusion: The Beginnings of Agentic centric Architectures

The journey from the original RobotoAPI to the new RobotoAgentAPI represents more than just a technical upgrade; it marks a fundamental shift in how we approach building intelligent applications. This step moves beyond simply using a Large Language Model as a text generator and begins treating it as a true reasoning engine, an autonomous worker capable of planning and executing tasks.

I’ve seen that the rigid, predictable world of if-else blocks and switch statements, while perfect for defined logic, falls short when faced with the boundless complexity of human language. By trading this old paradigm for an agentic one, doesn’t just make a chatbot smarter; but more resilient, adaptable, and context-aware. An agentic system moves away from trying to program every possible conversational path and instead towards the creation of a system that can find its own way. It is truly the “Secret Agent” stealthily working in the shadows to plan a mission and get the job done.

Take a look at the full code for the RobotoAgentAPI here

Time to cue up today’s track…

If you haven’t guess yet, the theme of todays post borrows from a 1966 earworm used in many Spy themed TV Shows and Movies.

“Secret Agent Man” — written by P.F. Sloan and Steve Barri and famously performed by Johnny Rivers — first gained fame as the theme for the U.S. broadcast of Danger Man (retitled Secret Agent) in the 1960s.

Over the years, the song has popped up in several movies and TV shows, keeping its spy-chic vibe alive:

- 🎬 Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995): A fast-paced cover by Blues Traveler plays during humorous moments—most notably when Ace is driving or interacting with animals.

- 🎥 Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997): The original Johnny Rivers version is included as a nostalgic nod to the 1960s spy genre that the film lovingly parodies.

If you grew up in the 90’s and are familiar with these two comedies, you may be humming along to the tune right now.