In this post, we’ll take a closer look at the technical components I built while putting together the U2-inspired BONO search system. Previously, we explored the PostgreSQL database and how I ran both semantic and lexical search queries on a table called movies. Now, we’ll dive deeper into the API and UI layers that bring this search system to life.

The BONO Search Database

To set up this database and the movies table, I followed these steps using an existing Azure subscription.

- Created an instance of the Azure Database for PostgreSQL flexible server

- Set up the necessary azure.extensions parameters in the database:

- AZURE_AI

- VECTOR

- PG_TRGM

- Created the necessary PostgreSQL extensions by running the following through the psql command line tool

- CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS vector;

- CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS azure_ai;

- CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pg_trgm;

- Created a “movies” table with the following columns (id, name, plot, plot_vector)

- Uploaded movie data from a csv file to the movie table using a PowerShell script

- Created an Azure Open AI resource

- Deployed a text-embedding-ada-002 model

- Configured the Azure Open AI resource url and key in the PostgreSQL database by calling azure_ai.set_setting method for each of these settings

- Vectorized the movie data from the plot column and store the result in the plot_vector column using another PowerShell script

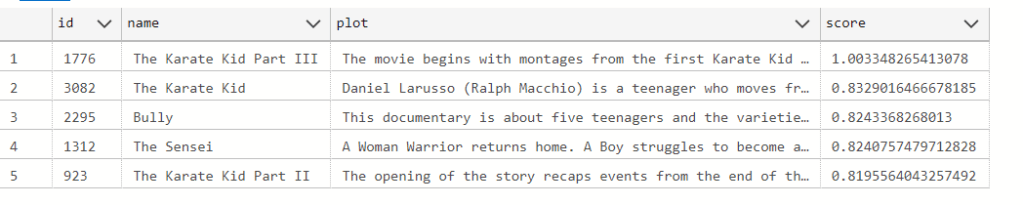

In the previous post, you may have noticed that the SQL queries referenced the text-embedding-ada-002 model multiple times. This is Open AI’s embedding model, which converts both plot descriptions and search queries from natural language into numeric vector representations. These vectorized representations, combined with transformer-based architecture, enable semantic search by allowing similarity comparisons based on meaning rather than exact keyword matches.

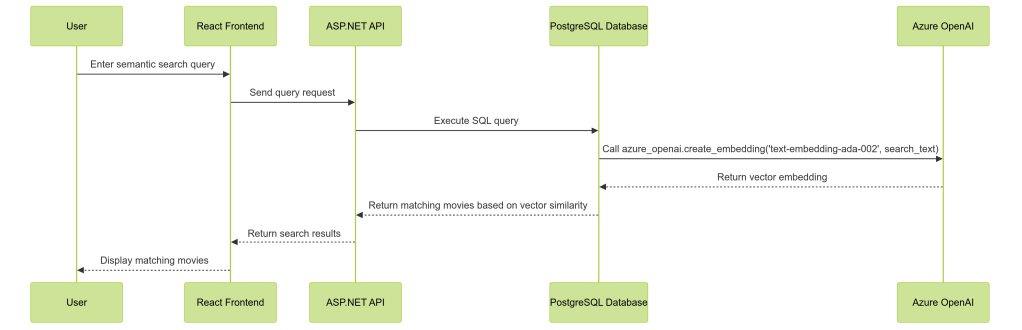

The BONO search system altogether comprises 4 main parts, namely a React UI, an ASP.net API, the PostgreSQL database server and of course the Azure Open AI resource hosting the deployed embedding model.

We can see how these components work together for a Semantic search query:

The BONO Search API

Having set up the database I began working next on the API. This was written in C# as an ASP.net (ver 8.0) API. A structure of this API can be seen here:

## Project Structure

BonoSearch/

├── Data/

│ └── MovieDbContext.cs # EF Core DB Context

├── Models/

│ ├── Movie.cs # Movie entity

│ └── DTOs/

│ └── MovieDto.cs # Data Transfer Object

└── Repositories/

└── MovieRepository.cs # Data access layer

└── Services/

└── MovieService.cs # Business logic layerAfter first implementing Semantic Search, I then added Lexical and Hybrid Search endpoints to expand the system’s capabilities. These queries are defined within the MovieRepository and accessed via the MovieService. This is the code to one of the methods from the repository

public async Task<IEnumerable<MovieDto>> SemanticSearch(string query)

{

var parameters = new NpgsqlParameter[]

{

new("query", query),

new("embedding_model", EMBEDDING_MODEL)

};

var movies = await _context.Set<Movie>()

.FromSqlRaw(@"

SELECT m.id AS Id,

m.name AS Name,

m.plot AS Plot

FROM movies m

ORDER BY m.plot_vector <=> azure_openai.create_embeddings(@embedding_model, @query)::vector

LIMIT 5", parameters)

.ToListAsync();

return movies.Select(m => new MovieDto

{

Id = m.Id,

Name = m.Name,

Plot = m.Plot

});

}

A key detail to note here is the use of Entity Framework’s FromSqlRaw method with parameters, ensuring that dynamic SQL execution is handled safely to prevent SQL injection. This approach maintains both flexibility and security while executing raw SQL queries.

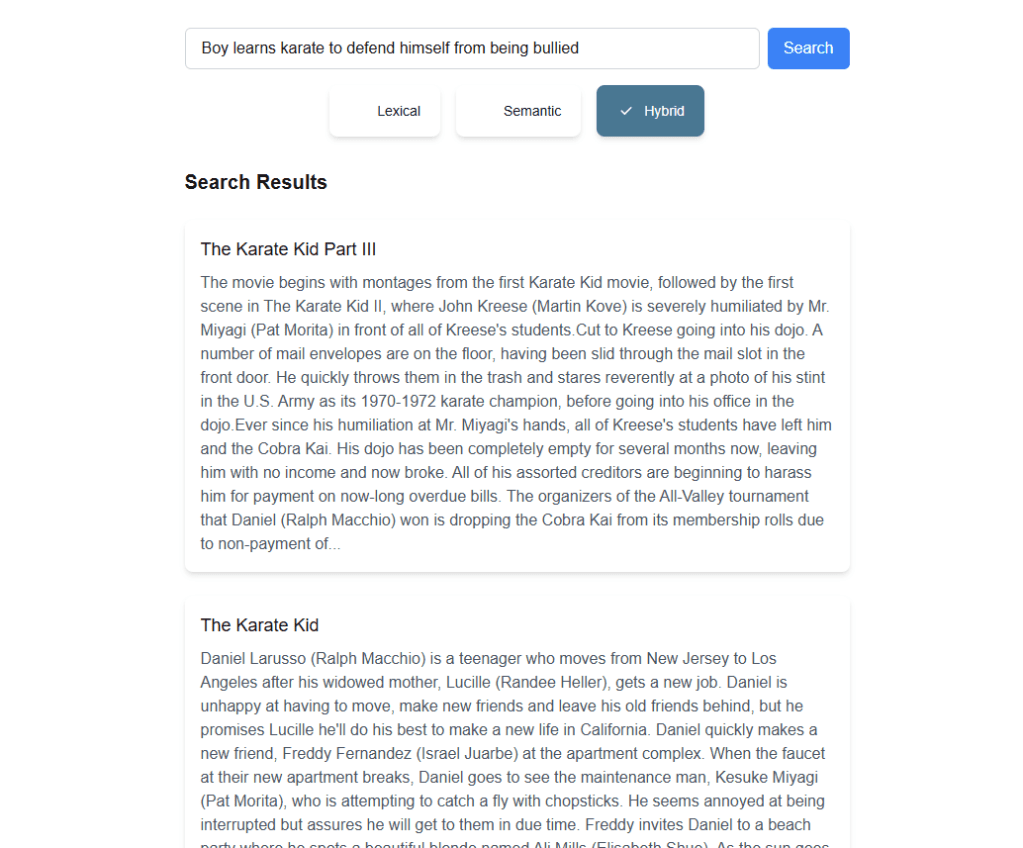

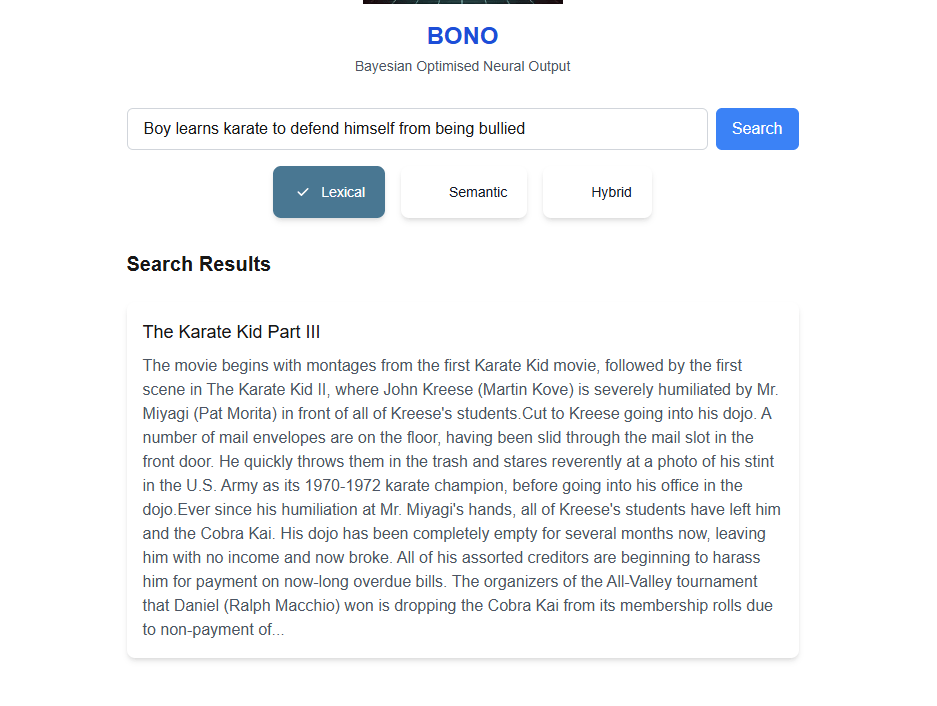

The BONO Search UI

As I’m currently learning to code in React, I decided to try and build the front end using React with Next.js as well as Typescript and Tailwind css. AI coding tools such as Cursor and Vercel’s V0 were a huge help in getting this completed and being able to converse with the AI model on elements of the code for explanations was an effective learning experience.

The React project contains 3 main components

- SearchForm.tsx – Responsible for:

- Rendering the main search components (input box, search button, radio selectors).

- Sending queries to the search API and updating

searchResults. - Passing

searchResultsto theSearchResultscomponent.

- SearchResults.tsx – Handles:

- Displaying the search results (movie name and truncated plot).

- Setting up an

onClickhandler to pass selected movie details toModal.tsx.

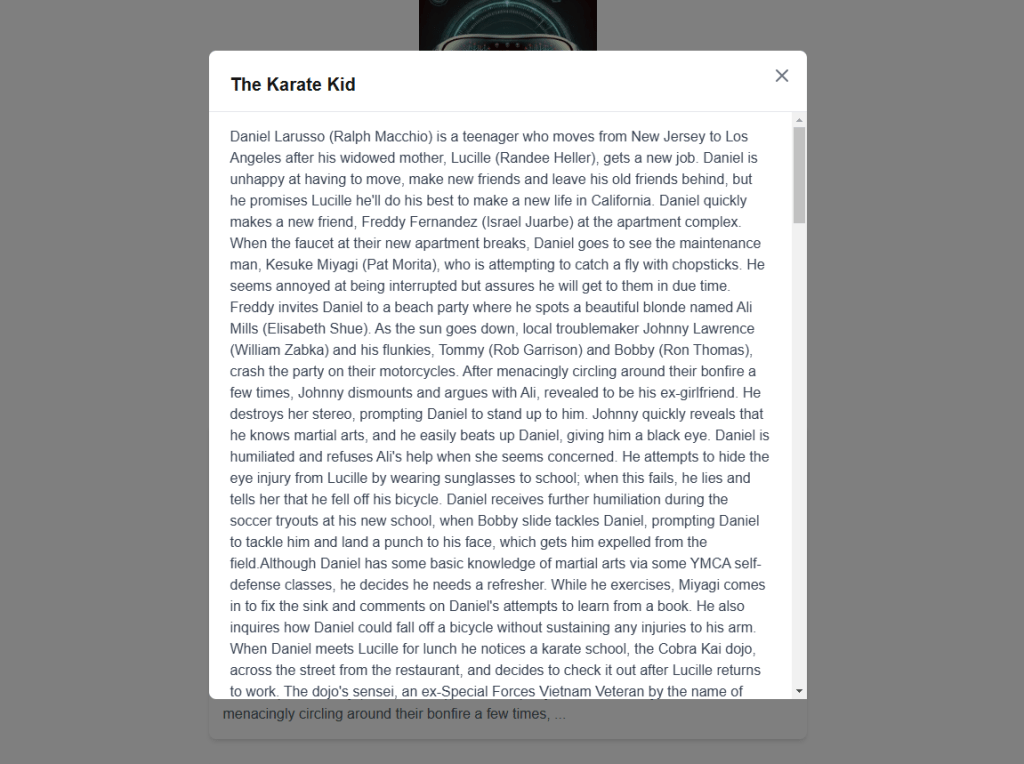

- Modal.tsx – Displays:

- Movie title as the modal header.

- Full plot description in a scrollable window.

The final UI looks as follows:

This brings us to the end of the first version of the BONO search. Some Key takeaways are:

- Semantic search does add value for the user but can bring in some unexpected results. We can lower the possibility of anomalies in the search results by filtering out results below a certain semantic score

- The Hybrid search gives the best results overall by prioritizing results with high Lexical and Semantic search scores

- Semantic searches do come at the cost of vectorizing both the Searched data and Search text. If the search text changes, the vector data would need to be re-updated.

- Azure PostgreSQL Flexible Server extensions abstract the Azure Open AI details from the consuming API and allow us to integrate with the Open AI services at the database level. This ensures a more secure architecture as only the database server needs to connect to the Azure Open AI resource

You may take a look at the project here: https://github.com/ShashenMudaly/bono-search-project

Before we wrap up, let’s acknowledge the inspiration behind the BONO search system—U2’s classic hit, ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’ is a song by U2, released in 1987 as the second single from their album The Joshua Tree. It’s a spiritual and introspective anthem that blends rock, gospel, and soul influences, featuring The Edge’s shimmering guitar work and Bono’s soaring vocals. The lyrics express a deep sense of yearning and searching—for love, meaning, faith, or something beyond the tangible. The song became one of U2’s most iconic tracks, resonating with listeners for its universal theme of an unfulfilled quest for something greater”…source: ChatGTP