In my last post I discussed the concept of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and showed my first steps towards creating a Chat API that would serve as the backend to a chatbot UI that I am building. I ended that post mentioning the limitations of that version of the API in the following areas:

- Context Window: The Chat API needed to draw on previous messages and responses in order to continue a conversation with the user

- Language Flow: The Chat API needed to direct the conversation based on whether the user mentioned a movie name, described aspects of the movie plot or responded to the user if they went off-topic during a movie discussion

For the context window problem, I chose an in-memory cache as my method of persisting the user’s conversation history beyond a single prompt. Having worked with Azure Cache for Redis in a recent post, I was now confident in using this method, though in most production Chat APIs we would likely use a database for long term persistence of a conversation (with permission from the user and the necessary privacy and SOC2 compliance considerations taken into account). I used the same cache that I had set up in the previous post, so if you want the details on how to set up an Azure Cache for Redis instance, I recommend taking a look at that post.

Having set up the cache, the next decision was to determine exactly what I planned to store. I thought about the conversation a user would have with the Chat API, something like the following example:

User: “What is the movie where a boy learns karate to defend himself from bullies?”

Chat API response: “The movie where a boy learns karate to defend himself from bullies is the Karate Kid“

User: “What is the name of the main character in that movie”?

Chat API response: “The main character in the Karate Kid is Daniel Larusso”

This seems a pretty straightforward interaction right? Well, from the perspective of a stateless Model, things can get a little tricky.

We know from the previous post which described the interactions between each of the backend components like the Model API, the Search API and the Chat API, the model produces the first response in the above interaction after receiving the movie title, movie plot and user’s query as part of its prompt. In order for the model to respond appropriately to the second query, it would need to be able to access the information it had from the first prompt as well. As the GPT model is stateless, it will not inherently have this capability and thus it will require the Chat API client to supply that information as part of its context.

It would therefore make sense for the Chat API to save into the Redis Cache the movie plot initially retrieved as part of the context window. In that way, when subsequent follow-up questions are asked by the user, they can be answered easily. It would also make sense to save the Model’s responses. Here’s an example where we can see the reason why:

User: “What was the second training method that Miyagi used to train Daniel”?

Chat API response: “The second training method that Miyagi used to train Daniel was having him sand a walkway that leads around Miyagi’s backyard. This was done with similar instructions on technique: moving his hands and arms in wide circles and deep breathing”

User: “Were there any more training methods that Daniel used?”

Chat API response: “Daniel practiced defensive techniques, learned physical balance by standing in a rowboat and trying to stay upright in the surf of the ocean, and practiced Miyagi’s crane kick at the beach.“

So as we see, the user’s second question is relative to the Model’s first response. The Model would need to produce a response that takes into consideration how it previously answered the user.

It made sense then at this stage to include the conversations as well as the context. But then things took a turn…

GPT Models and Large Context windows

For those of you who use ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot for your day to day chats, you would very seldom encounter a token limit unless you really tested it with a large file where the whole content of the file was important. The reason you would have not noticed the limitations of the underlying model with respect to token limits, is that we must remember Chat systems like ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot are not in themselves the large language models, but are systems that provide us, the user an interface into the underlying model. ChatGPT for example gives us the ability to send the model information in various formats even though the model itself may not even recognize those formats. For example, a GPT model does not inherently understand how to interpret a PDF but instead relies on the calling system to extract, pre-process and tokenize the underlying text in that PDF document . In the end, the model processes the tokenized version of that document and returns a tokenized result that will then get decoded back into human readable text.

What is a token limit?

A token limit refers to the total combined input and output tokens a model can process in a single context window.

Why does the token limit not usually get reached in ChatGPT?

Systems like ChatGPT prevent a user’s prompt from exceeding a model’s token limit by using various techniques to chunk out input to fit into a manageable context window for the underlying model to process. These approaches known as RAG techniques can range from a very basic partitioning of the user’s input into similar sized chunks or a more complex partitioning where chunks are partitioned based on the semantic relationship of sentences inside these chunks to each other. The overall intent is to have the model process the document one chunk at a time and combined the output of each processed chunk into a single coherent output. To the user, the RAG processing and the model’s limits are transparent.

This does not work in all cases though. There may be cases where processing the entire prompt is required to derive the correct output, and as a result, chunking would cause the model to generate a different output than intended.

Processing Movie plots with GPT-4o-Mini

So as mentioned in the last post, I chose the cheapest model I had access to in the Azure model catalogue -GPT-4o-mini, for my preselected region east-us. When I started to include the movie plot into the context window, I noticed the model taking a very long time to return its response. Granted, the movie plots I was querying were in the range of 15,000 characters, but performance slowed the more interactions I had with the API. It degraded considerably when I changed the topic to another movie.

Not all models are made the same

Initially, I assumed the slowdown was solely due to the increasing size of the context window. Although the response time did correlate with more plot data being added, switching to another model—GPT-4-32K—resulted in some performance improvement. Interestingly, GPT-4o-mini has a 128k token limit, whereas GPT-4-32K is limited to 32k tokens. At this stage, I could only presume that Azure’s API on the Standard tier reduces response times for certain models when handling large requests.

RAG Chunking

Dealing with a large context window was a challenge I would likely face at some point, so I decided to try a strategy to reduce it. I divided each movie plot into chunks of equal size and evaluated each chunk’s relevance to the user’s query. If a chunk was relevant, I added it to a shortlist; if not, I discarded it from the context for that query. To assess a chunk’s relevance, I made a call to the model and prompted it for a brief true/false response. By issuing many small requests to the model rather than one large one, I was ultimately able to reduce the overall context size for some queries. However, queries that required summarizing the entire movie plot still necessitated including the full text to generate a meaningful answer. In the future, I plan to refine this process further and explore techniques such as semantic chunking.

Dynamic RAG

Another strategy I applied was to dynamically fetch the movie plot based on the most current movie being discussed. This approach ensured that context was not built up unnecessarily for movies no longer in conversation.

Orchestrating a Conversation

This step required several tries before I evolved the code into a form of conversational orchestration. It turns out getting a model to seamlessly maintain a conversation or switch to a new one is not as easy as it looks with chatbots. The main challenge here is that every user prompt in my API could fall into one of the following categories:

| User Query | Category | Action |

| Tell me about tennis | Non Movie related | Inform the user this is a movie chatbot. |

| Tell me about the Karate Kid | Title of the movie is in the query | Look up the Plot based on the Movie title |

| Tell me about a movie where a boy learns karate to defend himself from bullies | Movie related based on a semantic question | Look up the Plot based on the semantic search |

| Who were the Cobra Kai students? | Movie related based on a current conversation | Look up the most recent movie title in the context window and dynamically fetch the plot to answer the question |

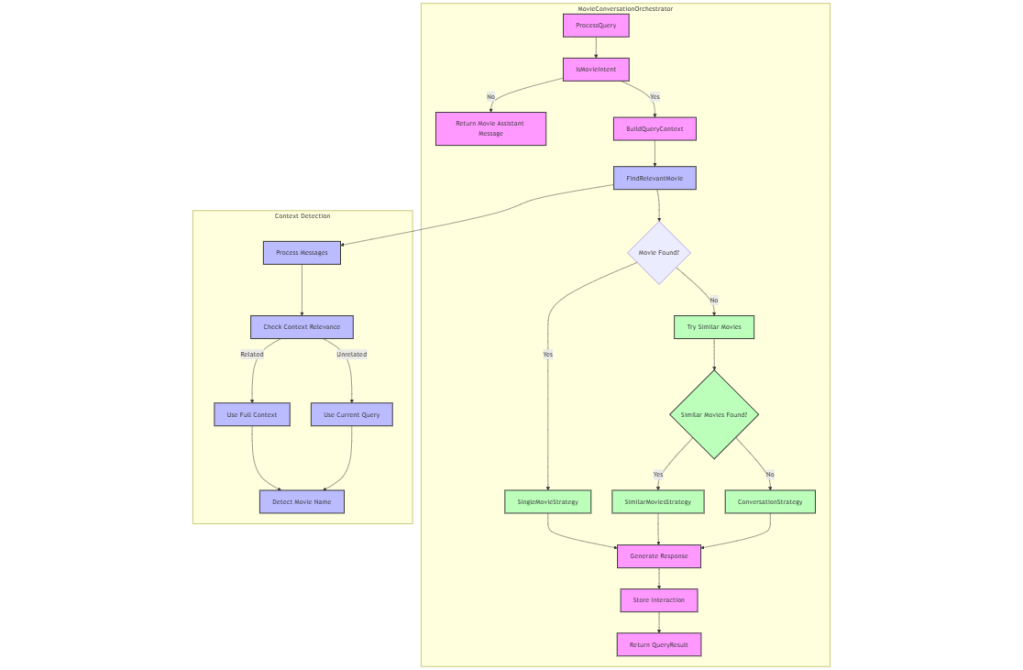

I therefore created a MovieConversationOrchestrator class that directs a user’s prompt to other specialized classes that perform the following functions:

- Checks if queries are movie-related

- Finds relevant movies from direct mentions of a movie name or context

- Applies different conversation strategies based on query type:

- Single movie discussions

- Similar movies comparisons

- General movie conversations

- Maintains conversation history

Think of the MovieConversationOrchestrator as a smart movie expert that:

- Understands when you’re talking about movies

- Remembers your previous conversation

- Provides relevant movie information

- Keeps the conversation focused on movies

Orchestration was therefore a key component of the Chat API because it determines when to apply RAG and how to optimize the context window in the chat.

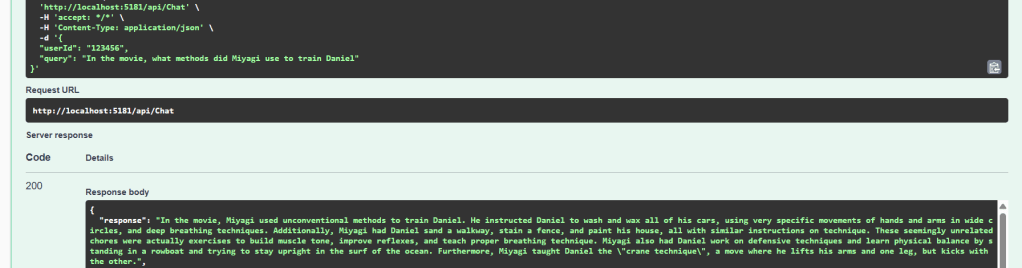

Let’s take a look at how the Chat API responds to a follow up prompt: “In the movie, what methods did Miyagi use to train Daniel“

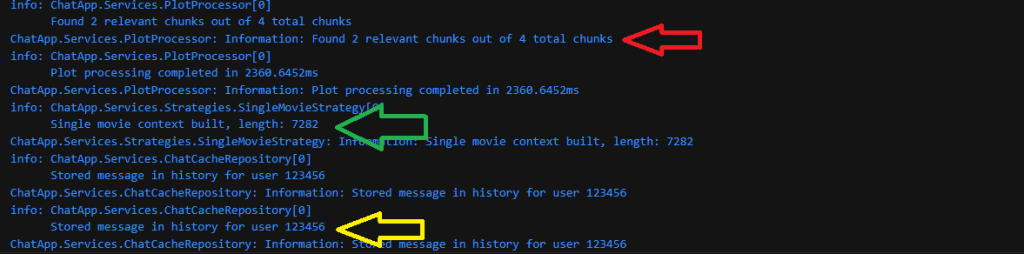

Looking at the Chat API logs we can see some of the underlying steps of the API:

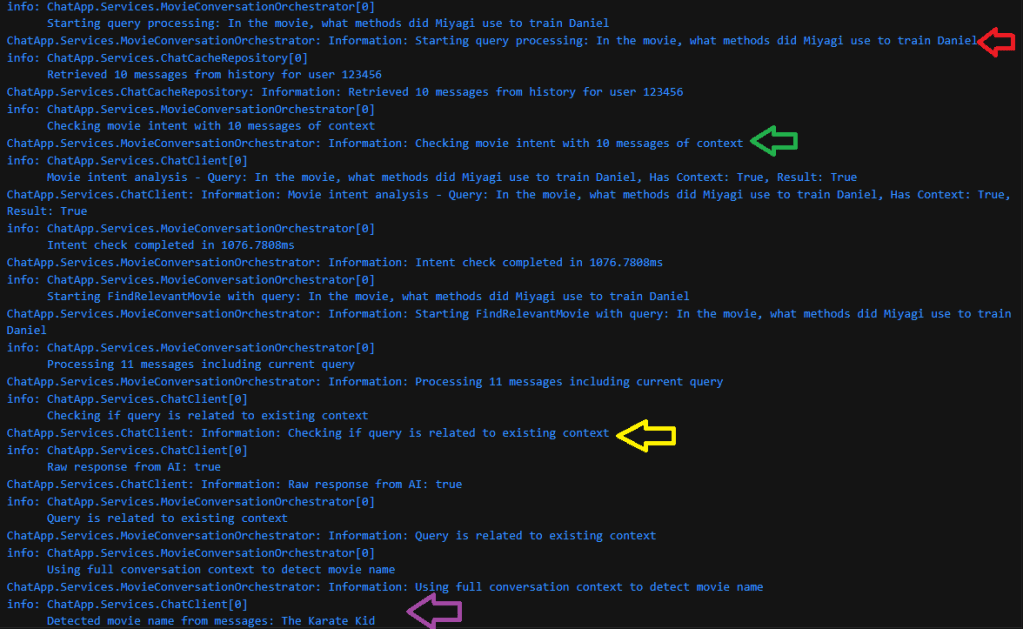

The arrows in the above log highlight the following steps:

- Red Arrow: User’s query

- Green Arrow: The Orchestrator searching 10 prior messages of the current conversation

- Yellow Arrow: The system uses the AI model to confirm if the query is part of the existing conversation

- Purple arrow: The system detects the conversation is about The Karate Kid

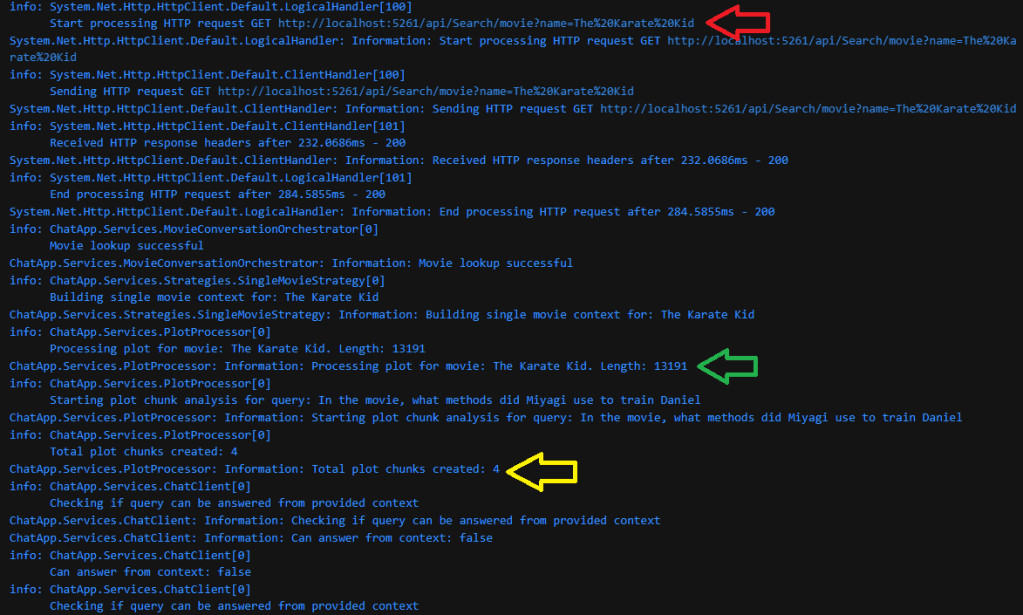

As we continue the logs, we see the next steps in the orchestration process:

- Red Arrow: Calling the search API by the movie name to retrieve the plot data

- Green Arrow: Begin processing the Plot of size 13191 characters in length

- Yellow Arrow: The system breaks down the plot into 4 chunks

And then in the final stage of the Retrieval and Orchestration process, the chunks are processed and the conversation is saved to the conversation history:

- Red Arrow: The system detects 2 out of the 4 chunks as relevant

- Green Arrow: A context size of 7282 characters is built for the model to process (reduced from a total plot size of 13191 characters)

- Yellow Arrow: Finally, after the response by the model is returned to the user, the system stores the user’s message and model response (without the plot) into the cached history.

Here we can take a look at the complete Chat API Architecture:

├── 1. API Layer

│ └── Controllers/

│ ├── ChatController.cs # Handles chat interactions

│ └── MovieController.cs # Movie-related endpoints

│

├── 2. Core Services

│ ├── MovieConversationOrchestrator # Main coordinator of all operations

│ │ ├── Query Processing

│ │ ├── Intent Detection

│ │ └── Context Management

│ │

│ ├── ChatClient # AI Service Integration

│ │ ├── Movie Detection

│ │ ├── Intent Analysis

│ │ └── Response Generation

│ │

│ ├── MovieSearchService # Movie Data Operations

│ │ ├── Movie Lookup

│ │ └── Similar Movies Search

│ │

│ └── PlotProcessor # Plot Text Processing

│ ├── Chunk Management

│ └── Relevance Analysis

│

├── 3. Strategy Pattern

│ ├── ContextStrategyFactory # Strategy Creation & Management

│ │

│ └── Strategies/

│ ├── SingleMovieStrategy # Single movie context

│ ├── SimilarMoviesStrategy # Movie comparisons

│ └── ConversationStrategy # General discussions

│

├── 4. Models

│ ├── MovieSummary.cs # Movie data structure

│ ├── ChatMessage.cs # Message structure

│ └── QueryResult.cs # API response format

│

├── 5. Interfaces

│ ├── IChatClient.cs

│ ├── IMovieSearchService.cs

│ ├── IContextStrategy.cs

│ └── IMovieConversationOrchestrator.cs

│

├── 6. Utilities

│ ├── MoviePlotChunker # Text chunking utility

│ └── LoggingExtensions # Logging helpers

│

└── 7. External Services Integration

├── Azure OpenAI # AI processing

└── Movie Database # Movie data source

To take a look at the full codebase please visit: https://github.com/ShashenMudaly/RobotoChatProject/tree/master/RobotoAPI

As we can see the process of managing a conversation with a Large Language Model is an intricate one and I take my hat of to the Chat systems out there that have perfected this process. It is also worth noting that there are frameworks like LangChain and Microsoft’s Semantic Kernel (which I’m hoping to delve into further in future) that help with the orchestration flow by eliminating the need to write this code out by hand. Despite some of the struggles I describe in this post, it was a great learning experience to see how to apply a basic RAG strategy to reduce the context window. I can see myself refactoring the strategy to applying Semantic RAG chunking at a later stage which would help to further reduce the relevant chunks by first grouping sentences according to their semantic connection to each other.

Please join me on my next post where we integrate this new Chat API with Chatbot interface that borrows its name from another 80s hit song.

And finally before I say good night, let’s cue up an 80’s favorite and the inspiration for this post’s title:

“Don’t Stop Believin‘” is an iconic hit single by American rock band Journey, released in 1981 as the lead single from their album Escape. Written by band members Jonathan Cain, Steve Perry, and Neal Schon, the song was inspired by the themes of hope and perseverance amid everyday struggles. It peaked at number nine on the Billboard Hot 100 and has since become one of rock’s most enduring anthems. Its appeal was further amplified by high-profile appearances in television shows such as The Sopranos and Glee, as well as in numerous films and commercials. In the digital age, “Don’t Stop Believin'” continues to thrive—garnering millions of streams on platforms like Spotify and Apple Music—cementing its status as a timeless cultural phenomenon and one of the best-selling digital tracks ever. – Source: ChatGPT