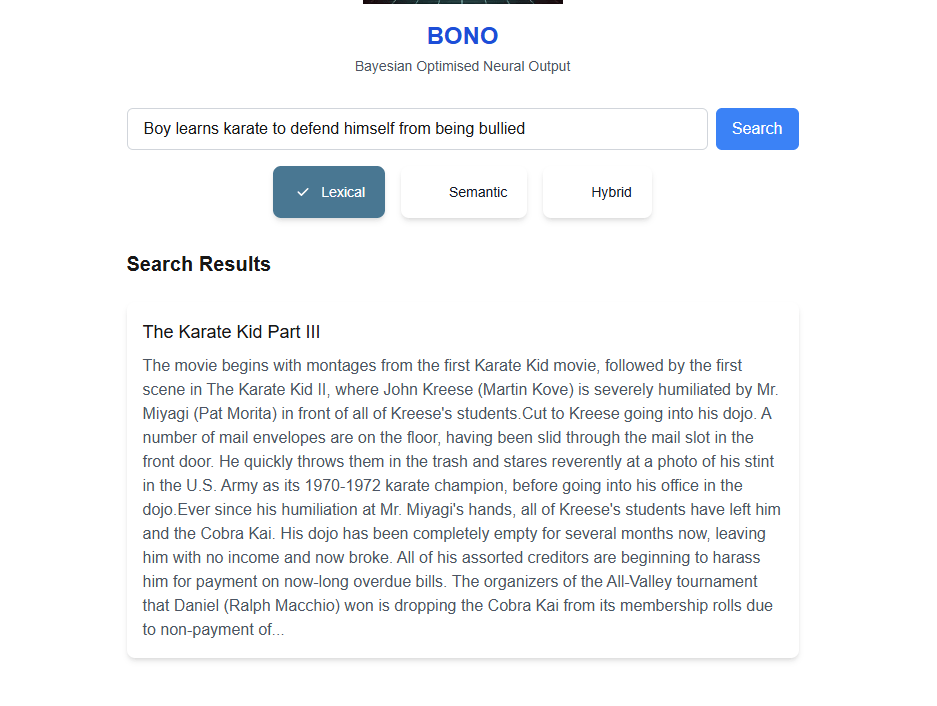

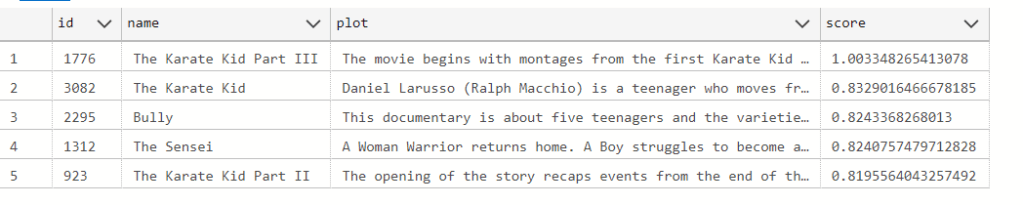

In my last post, we dove into the intricacies of integrating Azure AI Translator into the BONO Search system—showing how language detection and dynamic translation can bridge communication gaps and expand a single-language design into a multilingual experience. After grappling with throttled translation requests due to Azure’s quota limits, I also began to notice another inefficiency: repeatedly translating the same large movie plot descriptions during UI testing. This led me to a familiar challenge in cloud architectures—redundant API calls not only add latency but also inflate costs.

This blog post references an iconic lyric from Pink Floyd’s Money, “grab that cash with both hands and make a stash.” While the song isn’t about caching per se, I thought it was a fun way to play with the idea of building a stash (using Redis cache) to save money by reducing unnecessary translation calls. In this post, we’ll explore how integrating a caching layer can seamlessly optimize our architecture—ensuring every translation request is as efficient and cost-effective as possible.

The first step in setting up this change was to setup an Azure Cache for Redis resource in my resource group through the Azure Portal. The setup was pretty straight forward but there were a few gotchas on the free tier that I had to overcome:

- Private by Default:

- The resource is private by default, and the portal doesn’t offer an option to make it public. I struggled a bit with ChatGPT for a workaround but eventually found a solution on Stack Overflow that involved running a CLI command to enable public network access. Remember, it’s crucial to restrict access to your IP address range via the portal for security.

- Debugging Challenges:

- The free tier doesn’t provide an easy way to view cache content, which initially made debugging tedious—especially when verifying that my code was saving data to the cache. Once I implemented a read operation, I could finally check the results of my initial saves.

Design Considerations for Integration

With the Azure resource in place, the next step was integrating the Redis endpoint into the search input and translation workflows. I considered two approaches:

Integrating Redis Directly into the React Client:

One option was to introduce the Redis library into the React client, enabling the SearchForm component to directly save and retrieve values from the cache. While this approach would work, it’s a similar problem to what I encountered in my previous post. In other words the approach tightly couples the UI components to our cloud infrastructure.

This tight coupling means that if we ever decide to change our caching provider—whether switching to a different Azure resource or another cloud provider—we’d be forced to refactor the React UI.

Embedding Redis into the MAW API:

Another option was to integrate the Redis library directly into the Multilingual Autodetection Wizard (MAW) API, effectively incorporating caching into the translation flow. At first, this seemed like a natural fit and a simpler solution.

However, after further consideration, I decided against it. The challenge here was that cache entries would be indexed by movie names, while the Translation API is designed to be agnostic—it isn’t aware of the context of what it’s translating (such as movie plots). Its generic design makes it reusable for various translation tasks, so embedding caching logic here would compromise that flexibility..

Ultimately I concluded that introducing a new API—dubbed the Floyd Translation Cache Service—was the best approach to manage interactions with the Azure Cache for Redis resource. This design not only isolates the caching logic from the UI and translation service but also ensures that our architecture remains modular and flexible for future changes.

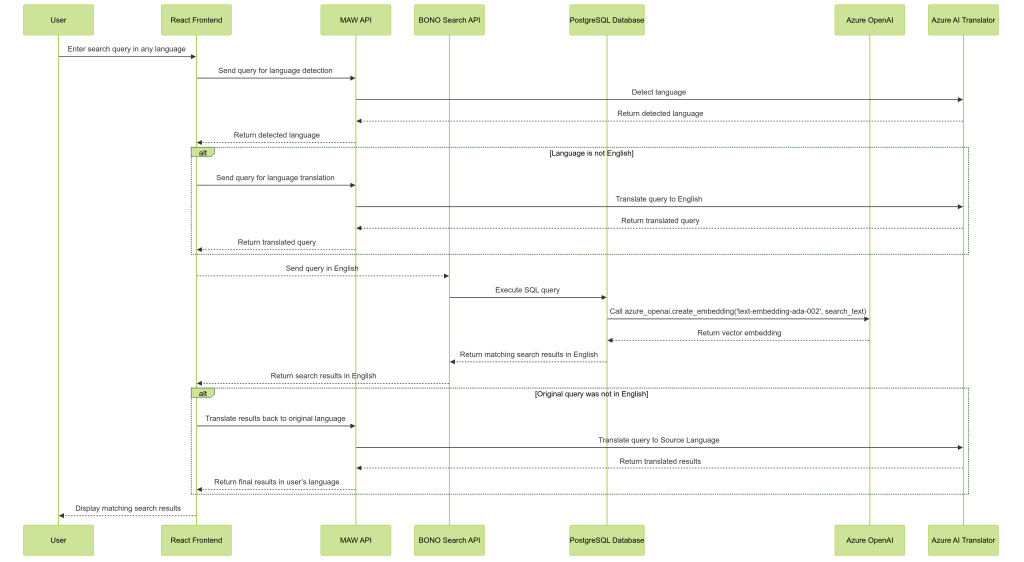

Here is how the new API fits into the Search and Translation workflow:

The Floyd Translation Cache Service

The API itself has 2 basic endpoints:

Save a Movie Plot:

Endpoint:

POST /api/TranslationCache/save-movie-plot

Content-Type: application/json

{

"movieName": "string",

"languageCode": "string",

"translatedPlot": "string"

}

Implementation:

public async Task SaveTranslation(string movieName, string languageCode, string translatedPlot)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Starting SaveTranslation for movie: {MovieName}, language: {LanguageCode}",

movieName, languageCode);

var startTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

var db = _redis.GetDatabase();

string key = GenerateKey(movieName, languageCode);

// This will automatically overwrite if the key exists

await db.StringSetAsync(key, translatedPlot);

var duration = DateTime.UtcNow - startTime;

_logger.LogInformation("Completed SaveTranslation in {Duration}ms", duration.TotalMilliseconds);

}

Retrieve a Movie Plot:

Endpoint:

GET /api/TranslationCache/get-movie-plot?movieName={movieName}

&languageCode={languageCode}

Implementation:

public async Task<string?> GetTranslation(string movieName, string languageCode)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Starting GetTranslation for movie: {MovieName}, language: {LanguageCode}",

movieName, languageCode);

var startTime = DateTime.UtcNow;

var db = _redis.GetDatabase();

string key = GenerateKey(movieName, languageCode);

var translation = await db.StringGetAsync(key);

var duration = DateTime.UtcNow - startTime;

_logger.LogInformation("Completed GetTranslation in {Duration}ms", duration.TotalMilliseconds);

return translation.HasValue ? translation.ToString() : null;

}

These endpoints leverage the StringSetAsync and StringGetAsync methods provided by the StackExchange.Redis client, ensuring efficient storage and retrieval of translated movie plots.

Integration with the React UI

After thoroughly testing the API, I integrated the Floyd Translation Cache Service with the React Search Form component. The following code snippet illustrates how the cache is utilized in the translation workflow:

// Translate plots back to the detected language if it's not English

const translatedResults = (await Promise.all(

results.map(async (item) => {

let translatedPlot = item.plot;

if (languageResult.language !== 'en' && languageResult.language !== 'unknown') {

// Try to get cached translation first

const cacheService = new CacheService();

const cachedTranslation = await cacheService.getTranslatedPlot(item.name, languageResult.language);

if (cachedTranslation) {

translatedPlot = cachedTranslation;

} else {

const plotTranslation = await languageService.translateText(item.plot, 'en', languageResult.language);

if (plotTranslation) {

translatedPlot = plotTranslation.translatedText;

await cacheService.saveTranslatedPlot(item.name, languageResult.language, translatedPlot);

}

}

}

The code above references a new CacheService class that handles the HTTP calls to the caching endpoints. This service first checks for a cached translation of the movie plot and uses it if available; otherwise, it makes a fresh call to the translation service, then saves the new translation result into the cache for future requests.

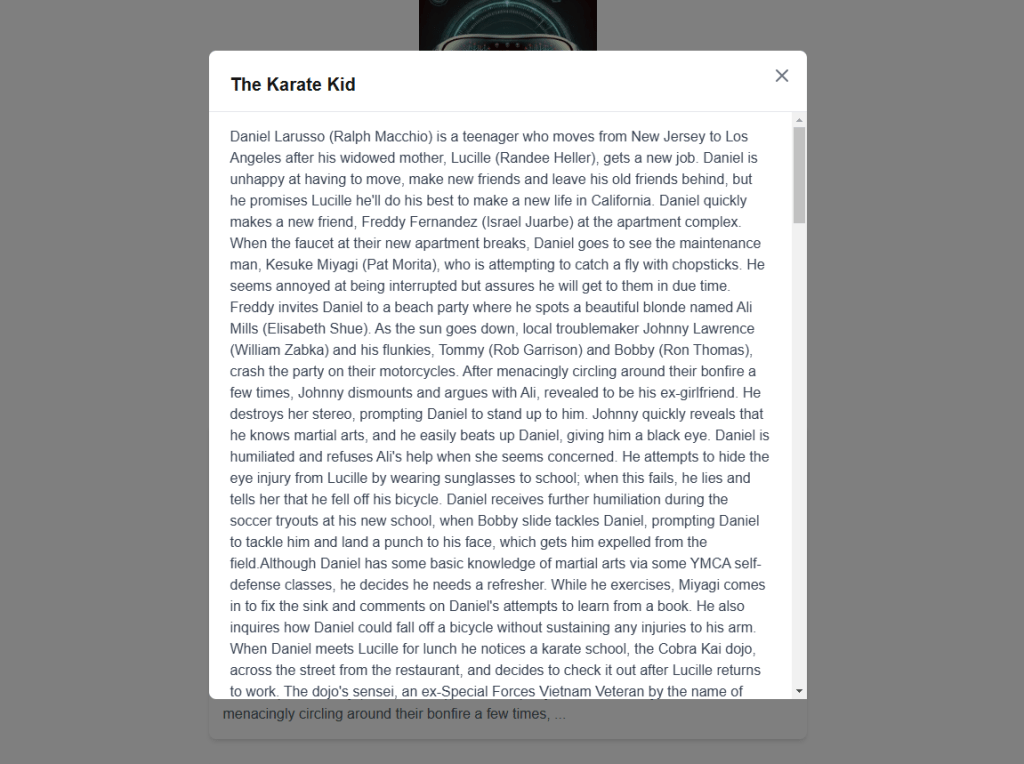

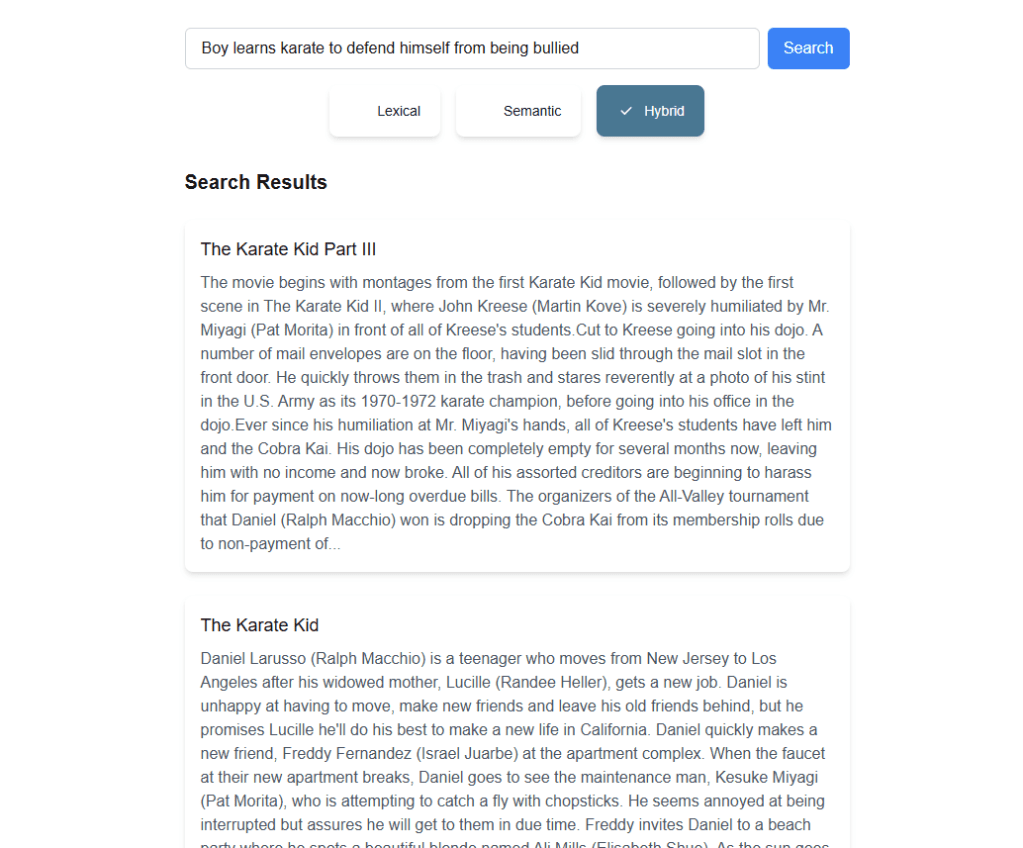

Demonstrating the Caching Mechanism

In the video below, you can see the caching mechanism in action with a Spanish search query. On the left is the browser window showing the search screen and its console output, while the right displays the Floyd service’s log output.

During the initial search, we observe the following:

- The Client side code logs a “not found” result in the browser when the Floyd Translation Cache returns no result,

- The Client code also reports a “Cache miss for RoboCop” message followed by a “Save successful for RoboCop” message —indicating that the newly translated Spanish plot for RoboCop has been cached.

- On subsequent searches with the same language (Spanish), the service logs a “Cache hit for RoboCop”

Simultaneously, the Floyd Translation Cache API logs mirror these events by showing the corresponding GetTranslation and SaveTranslation calls.

Conclusion

Integrating the Floyd Translation Cache Service addresses the challenges of redundant API calls and excessive latency in our translation workflows. By decoupling caching from both the UI and translation services and leveraging Azure Cache for Redis, I developed a modular and scalable solution that reduces operational costs while enhancing performance. Take a look at the code for the Floyd Cache Translation Service in my GitHub repo here and the React frontend changes here.

I’m pretty certain the approach will be reused upcoming projects and I look forward to sharing the next build with you…

And now, it’s time to Cue the next track…

“Money” is a standout track from Pink Floyd’s 1973 album The Dark Side of the Moon. Known for its distinctive bassline and unique sound effects—including the iconic cash register noises—the song offers a satirical take on wealth, greed, and consumerism. Its innovative production and incisive lyrics have made it one of the band’s most enduring and influential pieces. -Source ChatGPT