Exploring Semantic Search with Azure AI and PostgreSQL

Last December, I came across the Microsoft Learn Challenge Ignite Edition: Build AI Apps with Microsoft Azure Services. Since I had recently completed the Azure Fundamentals (AI-900) certification and was planning to take the Azure AI Engineer (AI-102) exam in January, this challenge seemed like the perfect way to sharpen my skills while working towards my next certification. The requirement was to complete all modules by the January 10, 2025 deadline, and I figured that even if I didn’t finish everything, it would still be a great head start for AI-102.

What really piqued my interest, though, were the modules focused on integrating AI services with Azure PostgreSQL databases. I had a basic understanding of vector stores, but I hadn’t yet explored practical implementations. I was also pleasantly surprised by how straightforward it was to extend Azure PostgreSQL to leverage Azure OpenAI services for tasks like data enrichment and vectorization. That immediately put Semantic Search on my to-do list—I wanted to build a working example and see it in action for myself.

What is Semantic Search?

Semantic Search allows users to find records in a data store based on the meaning of their query, rather than simply matching keywords. This enables users to describe what they’re looking for in their own words, and the system returns results that are semantically relevant, rather than relying on exact keyword matches.

Imagine searching a product catalog on a home hardware website. If you’re like me—a complete novice when it comes to DIY repairs—you might not always know the exact name of the product you need. Let’s say you search for:

“I need to replace the thing inside a toilet tank used for flushing because it is leaking.”

A Semantic Search system would interpret this query, recognize the intent, and return results for a flush valve assembly (yes, I had to ask ChatGPT for the right term here!).

Now, if the same query were processed using a traditional keyword-based (lexical) search, the system would need indexed product descriptions covering a wide range of variations—flush, flusher, flushing, leak, leaky, leaking—and even then, it might struggle to return the correct product unless the user used the exact right keywords.

By leveraging AI-powered vector embeddings, Semantic Search removes that burden from the user, making searches far more intuitive and improving the overall experience.

Naturally, I wanted to try this out for myself.

Creating the Bayesian Optimized Neural Output (BONO) search database

In keeping with the U2 theme of this post, I decided to create a search system with a name inspired by that famous rock front man with the wrap around sunshades. I chose movies as the content for my database because movie plot data provided good examples of text descriptions I could use for testing the sematic search queries.

I first set up an Azure PostgreSQL Flexible Server and created a table called movies, populating it with around 4,000 movie entries, including their names and plot descriptions.

Next, I used a PowerShell script to iterate through each record in the table and vectorize the plot field, storing the result in a new field called plot_vector (of type vector). This was done using the create_embedding function from the azure_openai extension. PostgreSQL handled the heavy lifting by directly calling the preconfigured Azure OpenAI resource and my chosen embedding model (text-embedding-ada-002).

The following diagram illustrates this process:

I did run into some issues with Azure OpenAI throttling my requests, as I was processing a large number of entries. To work around this, I modified the PowerShell script to process records in batches of 25, adding a 55-second delay between each batch. While this made the process take significantly longer, I simply let the script run overnight to complete processing all 4,000 entries.

The PowerShell script executed the following UPDATE statement:

UPDATE movies

SET plot_vector = azure_openai.create_embeddings('text-embedding-ada-002', plot)

WHERE id IN (

SELECT id FROM movies

WHERE plot_vector IS NULL LIMIT $BatchSize

);

The elegance of this approach lies in how the Azure OpenAI call is seamlessly integrated into the SQL statement. This ensures that the request is handled directly between PostgreSQL and the Azure OpenAI resource, rather than being made from the PowerShell script itself. By offloading this operation to the database, the process remains efficient, centralized, and eliminates the need for additional API calls from the script.

It was now time to experiment with a few semantic queries. My first test searched for the following phrase – Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied using a query as follows:

SELECT m.id AS Id,

m.name AS Name,

m.plot AS Plot

FROM movies m

ORDER BY

m.plot_vector <=> azure_openai.create_embeddings('text-embedding-ada-002',

'Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied')::vector

LIMIT 5

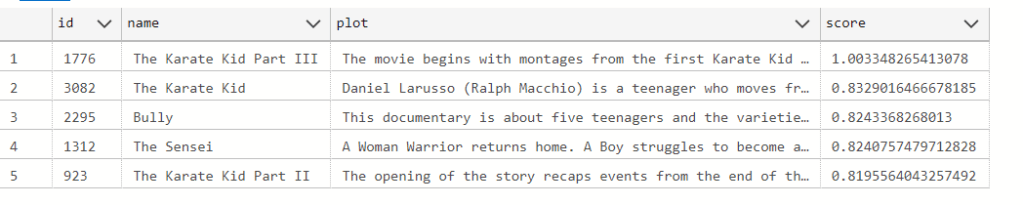

The results, unsurprisingly were:

What I found particularly interesting was that the plot description for that first movie title The Karate Kid did not actually contain the word “bullied” or any variation of it. Similarly, the description for next movie title The Sensei did not include “bullied” either but did contain “bully” and “bully’s”. This confirmed that the semantic search was working as expected, retrieving relevant results even when the exact keyword wasn’t present.

However, I soon noticed an unexpected anomaly. While the first four results clearly matched the search intent, the fifth result was surprising—Redbelt appeared in the list, even though its plot neither involved karate nor had anything to do with bullying. This movie plot instead describes the character learning Ju-jitsu which of course is a different martial art.

The results became even stranger when I searched for “Mammoth”, expecting the movie Ice Age to be the top result. Oddly enough, it wasn’t. The explanation became clear when I realized that the plot description for Ice Age didn’t explicitly mention “Mammoth”. But the real shocker? The Good Dinosaur ranked higher in the results.

Confused, I scanned The Good Dinosaur’s plot multiple times, convinced that a mammoth was never mentioned. Eventually, I turned to ChatGPT, and its response provided a fascinating insight into Large Language Models (LLMs).

Why Did This Happen?

Semantically, a mammoth and a dinosaur are related concepts (I can almost hear Jurassic Park fans sharpening their blades at this statement). While they aren’t genetically or biologically similar, they are both prehistoric animals, which makes them closer in meaning within the vector space of embeddings than other movies in the dataset.

This happens because semantic search represents words as numerical vectors in an n-dimensional space, and the distance between these vectors determines their relationship. The key word here is “probable”—semantic relationships are based on probability, not absolute definitions. This probabilistic nature is something that can be fine-tuned using parameters like temperature and top_p, which help control how loosely or strictly an LLM interprets relationships, ultimately reducing the likelihood of hallucinations.

A Lexical Search Comparison

Performing a Lexical search using the same search term as before “Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied” returned just a single result, the The Karate Kid part III as the plot of this entry contained all words in the search phrase. While the result is correct, it shows the weakness in the usability of the search method as it expects the user to refine their search term to get better results (and to incorporate Lucene syntax to convey their intent more accurately) . In this example there were other results that would have met the user’s expectation but did not get returned in the result set.

Lexical search however performed extremely well when the exact keywords were present in the plot description.

Here is the lexical search query using a different search term:

SELECT m.id AS Id,

m.name AS Name,

m.plot AS Plot

FROM movies m

where to_tsvector('english', m.plot) @@

websearch_to_tsquery('english', 'Dinosaur island')

ORDER BY similarity(m.plot, 'Dinosaur island') DESC

Limit 5

Adding the keyword “Genetic” to the search text significantly disrupted the results, returning the title Avatar as the only match. This happened because Avatar was the only entry in the dataset that contained all three keywords as the plot described an island, genetic connections between an Avatar and it’s human and the “dinosaur-like” creatures. Surprisingly, The Lost World, which seemed like a strong candidate, was excluded—likely because it was missing the keyword “Genetic”, despite being otherwise relevant to the query.

In the end, I realized that both search methods had their strengths, depending on the circumstances. Lexical search excels when the exact keywords are known, while semantic search provides better results when users describe concepts in their own words. To create the most user-friendly and effective search experience, the best approach would be to combine both methods.

Here’s what that hybrid query looks like:

WITH semantic_results AS (

SELECT id as Id,name as Name, plot as Plot,

1-(plot_vector <=> azure_openai.create_embeddings('text- embedding-ada-002',

'Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied')::vector) as semantic_score

FROM movies

),

fulltext_results AS (

SELECT id as Id, name as Name, plot as Plot,

ts_rank(to_tsvector('english', plot),

websearch_to_tsquery('english', 'Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied')) as text_score

FROM movies

WHERE to_tsvector('english', plot) @@

websearch_to_tsquery('english', 'Boy learns karate to defend himself from being bullied')

)

SELECT DISTINCT sr.Id, sr.Name, sr.Plot,

(COALESCE(fr.text_score, 0) + sr.semantic_score) as score

FROM semantic_results sr

LEFT JOIN fulltext_results fr ON sr.Name = fr.Name

ORDER BY

(COALESCE(fr.text_score, 0) + sr.semantic_score) DESC

LIMIT 5

What the above query does is create 2 records sets (one lexical based and one semantic) that get joined by their common movie name. The Semantic score and Lexical Text score of each movie are then added together and the whole result is ordered in descending order.

You may take a look at the Power shell scripts here: https://github.com/ShashenMudaly/bono-search-project/tree/main/data

In my next post, I’ll take this PostgreSQL-based search system a step further by building an API and a UI, bringing the BONO search system to life as a fully functional application. Stay tuned!